Time As Water, Love A Season

Seafood platter, carrying heels in your hand, taste of truffle, feet in the fountain.

The English bookstore in Rome was playing The Breeders when I walked in. Drivin’ On 9 is the song that most frequently arises from my subconscious, looping eternally somewhere in a mind trapdoor. I’ve been made aware that I might start absentmindedly humming it at any moment when I’m roaming an aisle or avoiding conversation or fantasizing. The cover of this album has a gelatinous red heart on it covered in spitty blood, with an insistent green background.

I’d walked around the block in Trastevere about three times looking for this bookshop. The blue dot of my destination was taunting me, kissing the blue dot that represented me on screen, but I was not kissing the storefront outside of the flattened map in my hand. In reality, I was pacing around and around, until, almost giving up, I looked up and the bookstore was, somehow, there. The experience had the feel of a middle grade fantasy novel wherein the mysterious shop appears at just the right moment, and the protagonist crosses the threshold, transcends. In a manner of speaking.

My plan had been to bring one book with me on the trip, then leave that book behind with whoever I was staying with or visiting, and then purchase a new book for the next leg. How cleanly that would have worked. As they say, the best laid plans…

The book I had been planning to take with me was The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy, an old cult classic recently reissued and reprinted, about a young American woman who goes to Paris in 1950-something. It appeared to have the wandering, frothy, and sharp combination I was looking for in a travel companion, but alas I could not secure a copy before I left.

So I improvised. By the time I got to Rome, I had finished the book Brad bought me in Paris, the first instalment of Deborah Levy’s living autobiography series, entitled Things I Don’t Want to Know. A pertinent line towards the beginning that secured its position in my handbag, Levy writes about “believing that Love, Great Love, was the only season I would ever live in.”

On its royal blue cover is a photograph of someone buckling their thin strapped mary janes, carefully. The photo is small, like the ticket for a museum. The black and white of it makes me want to say that it could almost be a Henri Cartier-Bresson photo, but in truth I don’t know much of Bresson except for what I saw in his gallery in the Marais. The photo on the cover is actually a still from Jean-Luc Godard’s film Vivre Sa Vie, which I have not seen.

At the Bresson exhibit, Brad and I walked a demure gallery route with large, vividly printed Bresson photographs. Brad told me a bit about Bresson’s importance in the history of photography, some context for viewing. After about thirty minutes of looking at the European landscape shots with dappled lighting, or one long shadow cutting through the frame, or a child, man, and horse making a satisfying triangulation, Brad admitted a frustration in not being more blown away by the photographs. Blown away; as in, physical impact, head blown off backwards, windy, rushing, enlivening. After all, this was one of the founders of street photography. Here lies an instance of expectation being the death of all genuine reaction.

Bresson spawned, to my understanding, a new way of approaching photography that was groundbreaking at the time (1930’s and onward). As with any artist breaking new ground, we’ve almost a hundred years later seen many spin-offs of his style, many photographic devotees creating works under the influence. Had we come to Bresson’s photography when it was fresh, had we not spent the last twenty years of our lives inundated with late twentieth and twenty-first century imagery, I suspect the photos would seem very different. More surprising. Or, maybe, we just were unlucky to happen upon an exhibit that featured primarily his landscape work, when we’re a pair of portrait hounds.

I had a similar feeling when, a few years ago, after hearing about the influence of French New Wave on Frances Ha (beloved to me) and also to endear myself to someone, I decided to love French New Wave. I’d seen the screengrabs of Anna Karina on tumblr all through my teenage-hood, I knew the gist, and I half-expected that watching the films would be like entering a historic homeland. Every minute, I waited for the idiosyncratic and singular spark, but it did not catch fire. The expectation of true love had stolen my ability to be bowled over. To be caught off-guard, to feel like you’re discovering new territory, a secret, a personal hand-shake with the cosmos, that’s real sexiness, real romance, real devotion. Funnily enough, however, my favourite Bresson photograph we saw was Bords de Seine, which looks straight out of a Rohmer movie.

We stayed at Liana’s apartment in Paris, and while she was at work we went to collect the keys from the fish store downstairs. She joked that the apartment sometimes smelled of fish. At the café soon after, drinking Liana’s hangover cure recommendation, Orangina, I read Levy, where she details a man she meets. She writes how “in Paris he worked in a fish shop. His bedsit in the 13th arrondissement always smelt of crab and shrimp he cooked most days.”

After Paris, in Stockholm, I picked up a copy of a zine, The Happy Reader, at a magazine store that had a backlog of them. It’s printed like an old national geographic, yellow borders and stiff newsprint. The issue I bought has an interview with Moses Sumney done by Jia Tolentino. I read the interview while drinking iced coffee before taking a ferry out to the archipelago to laze on rocks talking about birth with Zoe, and eat a raspberry dessert in a cottage’s backyard. This was after I had tried the röra Eiralin made (shrimp, dill, caviar, crème fraîche) served with steamed potatoes and pickled herring at Riley’s boss’s cottage in Dalarna, and before I tried blood pudding (boiled pig’s blood) chased with mimosas at brunch on the balcony of two lovely anarchists.

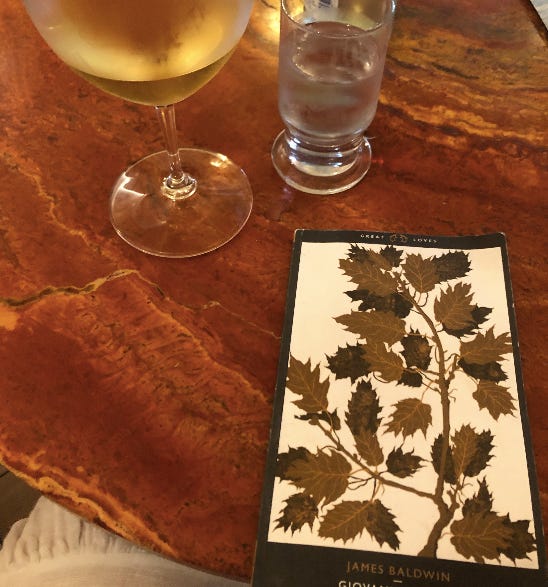

Sumney and Tolentino talk a lot about Gionvanni’s Room in the interview. I’d been meaning to read it, but never had. It’s one of those for me. It’s very important to read a book when the time is right, and not force it onto yourself. That would just be a disservice to everyone involved. Because the consumption of a book exists so spillingly in time, because you read some of it then tuck it away and start talking, take it out on the town with you in your new little bag, drink with it by your side, fall asleep to it, wake up with it while you sip a coffee, read it aloud to those around you if they’re lucky, it can really ruin the experience if the book isn’t congruous with the texture of your days while you’re reading it. This can’t always be predicted, but you can be strategic about it.

The bookseller in Rome, when I placed the thin volume on the table while The Breeders played, said, satisfyingly, oh, you’ve picked the best book in the shop. Everything, he continued, will now be, for you, before Giovanni’s Room, and after Giovanni’s Room.

When they meet, Giovanni and David have a back and forth at the bar, the kind that skates on and on with speed towards an inevitable blazing firework. First impressions can be anything, but sometimes they last forever. Hours before the white wine and oyster hangover cure, Gionvanni proposes something else.

“Time is just common, it’s like water for a fish. Everybody’s in this water, nobody gets out of it, or if he does, the same thing happens to him that happens to the fish, he dies.”

I was angling my reading material to be synchronous with the material of my days, my time, my water, my season. In Things I Don’t Want to Know, Levy writes from the vantage point of her trip to Majorca, where she goes alone to write, off season, to a small hotel that she’d visited years earlier to write something else. Amidst the citrus orchards and waterfalls and fireplaces, she writes and reflects. In Giovanni’s Room, the narrator David is reflecting too, from a rented house in the South of France. Both narrators feel a potent tragedy; David’s is clear, Levy’s is less so. David has banished himself from Paris, Levy has banished herself from London. Travel as seeking versus travel as self-banishment. Naturally, each of these books, in being focused on travel and displacement, are also concerned with their tonal inverse: home.

In Södermalm, Brad, Zoe and I shared a rented room. The owner of the apartment was a talkative crypto currency entrepreneur, half Greek and half Swedish, with a robust morning practice. He told us that the airy, high ceilinged apartment building we were to share with him for the next four days, was built in the 1600s and was used specifically as a home for people who worked in art and culture. It’s confusing to the North American sensibility when some crypto-meditator’s apartment stretches back further in history than one’s mind can properly conceptualize. Perhaps the idea of home has more of a sense of permanence to someone who has grown up around buildings that stay put for hundreds, thousands of years.

In these instances, you can really feel yourself as a fish, swimming through time. In the Roman Forum, listening to an audio guide point out whose temple is whose, I had to keep going okay, Emma, these are actually ancient ruins. These aren’t recreations, you’re not in Hercules, you’re not at Disneyland, you’re not in Las Vegas or on a movie set, these aren’t cartoon or papier mâché, these are the real deal. Ancient grapes were laid at the foot of this staircase as an offering to Jupiter. You’re standing where Julius Ceasar was assassinated. Mediated to hell like Bresson’s photos, I spent part of the travels trying to coax my genuine vision of the ocean of time out of my media-saturated psyche. A week or two later we swam in the bright turquoise ocean off of Paros, Greece, around the craggy Poseidon rocks, gazing at the mountains of Naxos, the neighbouring island. By then, my perception had adjusted to the shocks of beauty, filtering less through a screen of contemporary references. Same feeling: looking at the landscape which birthed myth. Coming up for air, speaking for the ancients, Liana said this landscape really makes you understand wanting to leave a legacy.

Being away from home, Levy can consider more clearly what such an abstract idea such as home might mean. Touching on motherhood, she quotes Marguerite Duras:

“A house means a family house, a place specially meant for putting children and men in so as to restrict their waywardness and distract them from the longing for adventure and escape they’ve had since time begun [...] The house a woman creates is a Utopia. She can’t help it–can’t help trying to interest her nearest and dearest not in happiness itself but in the search for it.”

So, a house is a safety mechanism created by women to prevent adventure and escape. Or to protect from it, depending on the vantage point. Likely, both, because adventure and escape can go two ways. That’s so largely what Giovanni’s Room is about, isn’t it? Safety and risk, two polarities. Trying to balance them, trying to achieve both.

David of Gionvanni’s Room has been the child that Duras speaks of, and now is that man. He walks the Seine, cold, on the comedown, bereft and full of adventure, longing to be behind the doors to the family homes he passes. He is in the adventure and yet in that moment does not want it, craves safety. Having left the family home, the only way he can imagine having that safety again is to recreate the family structure, this time as the father.

“I wanted children. I wanted to be inside again with the light and safety, with my manhood unquestioned, watching my woman put my children to bed. I wanted the same bed at night and the same arms and I wanted to rise in the morning knowing where I was. I wanted a woman to be for me a steady ground, like the earth itself, where I could always be renewed. It had been so once; it had almost been so once. I could make it so again, I could make it real.”

He cannot imagine his way into a different version of safety other than to reproduce the societal standard. Those based, debased wants of comfort, they only really kick in when one is feeling totally low. When the hangover threatens, when loneliness spikes, when physical and emotional discomfort encroach. They’re instincts of survival. But as soon as one is feeling rested and fed, cared for and chilled out, the longing for adventure reappears.

When I was feeling ill, in various ways from various exertions, I didn’t dream of home, though. I dreamt of an oversaturated fantasy. In Paris after a long night, practically sweating rosé, I fell asleep on a pull out couch with visions of endless wicker café chairs and circular tables. Rows upon rows of the city’s signature comets of socialization, the tiny cups of espresso, the frothy espresso martinis, the stacks of bread bread bread, the carafes of house white, a thousand hands reaching out with lighters to spark the end of my vogue. All the pleasures of waking hours roil into something rotten when one is feeling the consequences. And in Greece, a similar reaction. Play-acting as that painting Young Sick Bacchus, metaphorically clutching my grapes and wearing my laurel, hitting pillow in the early hours of morning. My dreams a disembodied consciousness flying through the rambling all-white Grecian towns, organized in a sacred geometry of turns and steps and two story now one story now four story buildings, stacked and labyrinthian, royal blue accents like Levy’s book cover.

A home is a shelter from the realities of the world, when the realities of the world are harsh. Physical difficulty: that’s what it is to live, and to live is also to try to invent ways to assuage it.

In Florence, the room I stayed in was rather like a boarding house - there was a person who lived there, plus a variety of rooms with people moving in and out. It was a very old and lovely house with a wide marble staircase and a straight visual line to the Duomo, but it was so, so hot at night that I developed a routine to make sleep even remotely possible. The routine was as follows: before I left for the day, I filled a massive plastic water bottle with water and put it in the freezer. When I came home sweating and swooning late at night, I took a cold shower, then got the frozen water bottle from the fridge, put the fan as close as possible to my bed, stripped naked, put a damp cloth over my body, and cuddled the frozen water bottle like an elemental teddy bear.

“People can’t,” Baldwin writes, and David says, “unhappily, invent their mooring posts, their lovers, their friends, anymore than they can invent their parents. Life gives these and also takes them away and the great difficulty is to say Yes to life.”

Is it true that we can’t invent our lovers and friends? You can pursue them, but I suppose you can’t summon or create them, the way you can draw a muscular figure out of marble. You can only put yourself in the right position to walk in their line of sight, you can only say Yes when life gives, you can only go to Paris.

In Paris the girls were wearing rings of sparkly beads, strung together like mermaid personalities, and chunky pendants thumping between their collar bones. I met everyone one night at one bar, and again the next night at the next bar. The two meetings remain in my mind like two castle towers standing next to each other, connected by a thin bridge. In the first castle, each person has one set of hang-ups, dramas, concerns, anecdotes, disclosures, and in the second castle, these have all shifted. Ex-pats, from Copanhagen and Taiwan and London, etc. Bring your wine glass into the street, bisous, bisous. The first castle tower, rosé, endless glasses of rosé. The owner running around in a tie dye t-shirt, a wizened old dog wobbling under everyone’s tables and feet. The owner would stoop down, carrying a plate of braised quail in one hand, scoop the dog up with the other, drop him off in his dog bed.

The next night, the next castle tower was a severe silver bar that dazzled me instantly upon entrance. High stools, low lighting, charismatic servers and bartenders that gave the impression that they were at a party together, dressed in matching crisp whites, and just happen to be serving us during this party. A myriad of shifting dramas that have unfolded, revealed covertly and in choppy anecdotes over slushie tequila cocktails in short glasses, in coy cigarette encounters on the cobblestones outside.

Perhaps the trouble with travel as enacted fantasy is that banality is impossible to escape, though it’s our greatest wish to escape it. The great difficulty to say Yes to life when, as Baldwin writes, “one of the real troubles with living is that living is so banal.” Banality is different from discomfort, or pain. Banality is somewhere, maybe, between the plush comfort of a warm home, and the wind-whipping thrill of wayward adventure. What might banality look like? Being hungry and not being able to find the restaurant you were recommended, settling for a middling slice of pizza. Unbearable blisters from your new strappy sandals, and still kilometers to go. Chafing beneath the summer dress. Running out of water, no fountain in sight. There’s the vision of beauty, and the mortal attempt to inhabit beauty.

But the realities of the world, can they be so tender, radiant, and extravagant too?

Neptune’s marble hands grabbing marble ass-flesh, indenting it, beloved detail of a towering sculpture. The long blonde hair of the Swedes swinging over their shoulders. Cupid and Psyche decked out in light turquoise and soft pink wings, brocade gemstones. Stewed Grecian grapes grown on the balcony of the restaurant, served atop soft tart yogurt, on the house. Green slushie shot, on the house. A spoonful of vanilla in a glass of water, on the house. Bright lake in the centre of a forest, a castle peering over a cliff and an elfin child slowly eating a large piece of bread, waving. Sitting on the stone edge of a canal, dozens of plastic cups of campari and paper plates of cichetti. Neon highway underpass of the outdoor club. Pastis at midnight. Scandi summer 4am walk home, has the sun yet to set or already risen? Ashtray made of a seashell. So many tabletops. Caviar on chips and paper bags greasy from the pastry. Horses on the horizon. Houses coloured from the copper mine down the road. Seafood platter, carrying heels in your hand, taste of truffle, feet in the fountain.

There are moments where the fantasy is inhabited, where we might escape the banality, and those we treasure. I love the way that Hella, David’s fiancé who is absent for much of the novel, is introduced. She bears a remarkable similarity to Sally of The Dud Avocado, in this introduction. “That was how I met her, in a bar in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, she was drinking and watching, and that was why I liked her, I thought she would be fun to have fun with.”

One night in Paros, four of us went to have cocktails on the other side of the island. The bar had a large outdoor space of signature Grecian limestone whitewash, with a ceiling made of lanterns and magenta floral branches from the surrounding trees. I drank a strawberry daiquiri and asked what everyone’s relationship is to expectations and fantasy. We started talking about the ways that what one fantasizes is just as strong a marker of time as things that quote unquote actually happen. That what one imagines or daydreams about can have real ramifications, can change you, your perspective, how you are in the world, can be a stake in the waters of time the same way a material memory can. The moments detailed here are just as tangible now to me as any fantasy.

In Stockholm we got to know the Swedish friend group of our ex-pat friend. At the bar in Paros, I started to tell a story about a night at a dive bar. The two Swedish friends I was seated next to, matching in their dashing nature, told me that once, while they sat in this exact same spot, they saw the Stockholm-born actor Alexander Skarsgård wearing a green soccer scarf (the same kind one of the boys had strung around my neck on a different night, different bar) cheering for their team just a few tables over. When I told this to the table in Paros, my friends said well you basically saw Alexander Skarsgård, then. Same bar, same seats, same boys, what’s the difference? If negotiating with fantasy is all we do when traveling, why not stretch it to a satisfying conclusion? In my notes app I once wrote ‘a daydream is a flare of faith.’ I have no idea now whether this is a quote or if these words are my own.

I ended my trip reading the initial coveted novel on the beach in Paros. Liana pulled from her bag the book I had sought after to start the trip: The Dud Avocado. She lent it to me for the duration of the beach, but due to the overwhelming need to swim every half hour, drink warming white wine, listen to Eve Babitz read aloud, chop open a watermelon, and talk incessantly, I only got twenty pages in.

EMMMMMMMMMMMA! Goddess of words 🫶🏾

❤️